"Information has to be organized, and how it is organized makes a difference."

Zotero is a free program for saving citations, taking notes, and formatting reference lists. Once you download Zotero and install a browser connector, you can use it to save webpages, articles in databases, and book references from the library catalog, library databases, Amazon, or Google Books. Your collected references can be synced from one computer to another and can be accessed online through any web browser. Sort your references into project folders, tag them, add annotations and, when you want to create a reference, simply drag them into a document and choose a format. See the Zotero Quick Start Guide to get started, try our very brief general guide to Zotero, or see Jason Puckett's guide for more tips and strategies.

A note for Zotero users - you can set up Zotero to recognize content in our databases by clicking on Edit > preferences > Advanced, and adding under Resolver this URL: http://worldcatlibraries.org/registry/gateway

Zotero works with Google Docs. An optional plug-in for Word (or Open Office) is also available. Open Zotero and install the plugin found under Tools - Options - Cite. The plugins will then be found in Word under the Add-Ins tab (PC) or under the scripts menu (Mac).

Want more information? Contact a reference librarian.

NOTE: Though Zotero originally was developed as a Firefox plugin, it now must be downloaded as a standalone program with a Firefox connector installed as an add-on.

While you can track sources and take notes in any of a number of ways, at some point you need to sort them thematically to create a narrative about them - in other words, to write your literature review. How you do this is a matter of personal choice. Here are some ideas.

You need to create citations in the form most commonly used by political scientists.The Chicago Manual of Style (or a refined version developed by the American Political Science Association) presents source information in a way that suits scholars in this discipline best.

Remember, if you use Zotero you absolutely MUST edit the results. There will be goof-ups that need to be fixed.

For the most basic kinds of citations, we have a quick guide that gives examples. For more examples, consult the Purdue OWL's guide. Or delve into the manuals shelved near the reference desk for all the details - especially the big fat Chicago style manaul.

There are at least three reasons why writers cite their sources:

When you are preparing a document,use this checklist to be sure your citaitons are complete.

Because scholars in different disciplines emphasize different things when they read citations, there are many different styles. The MLA style, used for literary studies, makes sure author names and page numbers are provided in an in-text citation because the authorship and exactness of a quotation matters; the APA style used in psychology and other social sciences include the year of publication, because when research was conducted is considered particularly significant. The Chicago Style is used by disciplines such as political science, history and religion, which value sources so much it's common to put all the information about a source in a footnote as well as in a bibliography at the end of a paper.

The trick to effective writing using sources is remember that sources come from people, and the people you cite are helping you build a case, make an argument, or explain ideas. Use your sources strategically - as allies and informants.

From a reader's perspective, it's helpful to know who you are relying on, so try to introduce your sources with a signal phrase that tells your reader where the source came from and why it's worth paying attention to. Here are some examples.

Though sources are important, how you talk about them in your own words is paramount. If you are paraphrasing sentences from a source, be careful that you aren't copying the sentence and just changing a word here and there. Even if you cite that source, copying too closely is considered plagiarism. Limit your use of direct quotations to those instances when accuracy of a key phrase is important or when you want to call attention to the particular wording of an idea.

In most cases, your best bet is to know your material well enough that you can set a source aside and write about its ideas in your own words. Otherwise, you run the risk of simply compiling a data dump or creating a patchwork of quotations. When you can sum up the gist of a source - its main point - instead of quoting from it excessively, that will save your reader time and will demonstrate that you really know the material. It will also leave more room for you to put your own stamp on the ideas you are writing about.

For more about how plagiarism is handled at Gustavus, see the college's Academic Honesty Policy.

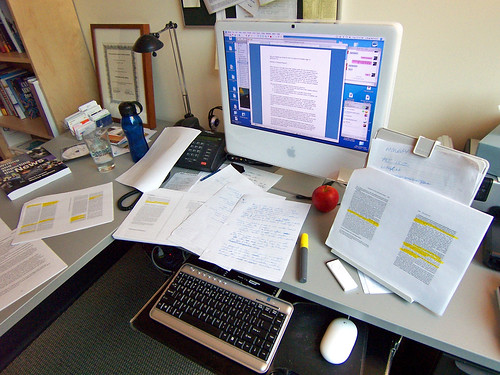

photo courtesy of Alfred Hermida

Joining a conversation already in progress may be a lot of work, plowing through databases and dense prose, and figuring out the rules for introducing your readers to all the other voices that contribute to your ideas can be a time-consuming pain.

But in the end research is valuable - not just for making a point or getting a good grade, but for finding stuff out that can help you make up your mind, because then you have the tools to use your ideas to make the world a better place.

photo courtesy of Joanna Penn

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0